Sampling the oceans

Save the corals

n April 2019, Bry Wilson stood on the deck of the research vessel, squinting in the sun. Wilson, a marine biologist at the University of Oxford, felt both exhilaration and fear at the thought of the small plastic trunk stowed away on the boat.

1,000 miles across the ocean to bring a species back from the dead

Coral Complexities

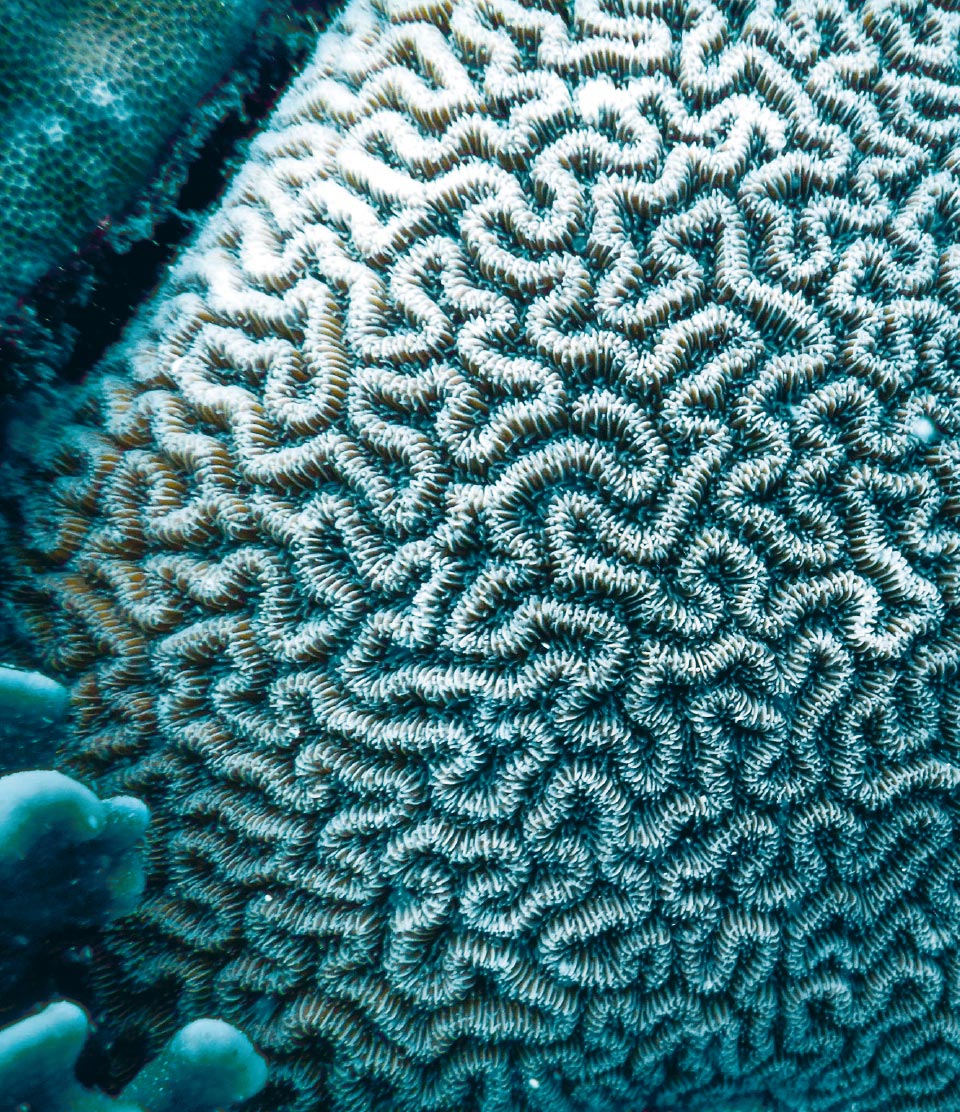

The Chagos Archipelago is home to more than 300 species of coral. These animals are at the heart of a complex marine ecosystem that supports a wide variety of reef-dwelling creatures. A coral exists in “this incredibly beautiful symbiosis” with the organisms that live in and around it, Wilson says.

“All these organisms live on and within the coral,” he adds, from bacteria, viruses, protists, grazing protozoa, algae and fungi, to crabs, shrimp and fish. “All of those have their own little microbial communities, and they all mix. Corals are immersed in this incredible microbial soup. It’s an extraordinarily complex ecosystem. Trying to tease apart what’s going on in that crazy chaos is something that really drew me in.”

Wilson has always had a passion for science. “When I was five, my father built me a wee lab out of breeze blocks in the back of the garage,” he recalls. “I filled it with all manner of trophies from the surrounding fields and forests – discarded birds’ eggs, owl pellets, skulls, you name it.” In 2005, after reading about the spread of coral diseases, he impulsively packed his bags and flew to the other side of the world to research the impact of disease on the Great Barrier Reef. Sixteen years on, saving the corals has become his life’s work.

Wilson has been incorporating molecular testing into his coral research since early in his career. When reports of diseased corals began appearing in scientific literature in 2005, he applied for and received a three-year fellowship to study the impact of the pathogenic bacterium Vibrio coralliilyticus (“coral dissolving” in Greek), on the Great Barrier Reef and in the South Pacific. In the course of that work, he developed a real-time PCR diagnostic assay for checking levels of an enzyme that the bacterium used to break its way into the coral tissues, potentially revealing whether a coral was infected before it showed symptoms.

Since then he’s used molecular testing and bioinformatics to try to understand corals’ genetic responses to a range of threats, from pathogens to climate change.

“Corals are immersed in this incredible microbial soup. It’s an extraordinarily complex ecosystem. Trying to tease apart what’s going on in that crazy chaos is something that really drew me in.“

Bry Wilson

RNA from raft to reef

The research vessel is a former North Sea firefighting ship that has been repurposed as a patrol vessel – and seasonal research platform. To create a cool refuge for RNA and DNA sample processing in the sweltering humidity and heat of the tropics, they built a lab on the deck out of a shipping container. It holds an air conditioning unit, a small freezer stocked with ice packs, a fridge, a worktable and benches. It’s equipped with a centrifuge, various lab paraphernalia and molecular testing tools, including QIAGEN DNA extraction kits. “The great thing about the QIAGEN kits is that they come with pretty much everything you need,” Wilson says.

He does some sample processing underwater. One approach has been to put coral tissues in an RNA stabilization reagent right there at the reef, because “I’m always trying to find ways to cut down on the amount of time from sampling to processing.”

Other times he processes samples while bobbing in one of the inflatable rafts they use to visit reefs the ship can’t access. “I’ll tell you, pipetting 100 microliters of a compound or chemical when you’re in an inflatable boat in a two-meter swell is a challenge.”

The Chagos Archipelago

Wilson is a member of the Bertarelli Foundation’s marine science program, which draws scientists from around the world to collaborate on research projects in the British Indian Ocean Territory Marine Protected Area.

All fishing and extractive industries are prohibited in this 640,000 sq. km region. Occupying just 60 sq. km of the vast expanse are the Chagos Archipelago’s 58 tiny islands and atolls. They’re uninhabited except for Diego Garcia atoll, which is home to a US Navy support facility.

The lack of human activity in the region makes it one of the world’s best places to study the impact of climate change. “The opportunity to work in this area is like a dream,” Wilson says. “It’s like an ecosystem from 50–60 years ago.”

From lab to genome

Plastered with permits and airline stickers, the trunk holding the coral samples made it back to the molecular lab at the University of Oxford’s John Krebs Field Station, where the samples were stored in a -80°C freezer. Not long after, he got word he’d been awarded a $25,000 QIAGEN research grant. He used it to fund the sequencing of the genome of the coral in the trunk. The grant came with 16 hours of lab work at QIAGEN’s genomics lab in Hilden. So he shipped the corals to Germany, along with detailed instructions about how to handle the delicate samples.

The results arrived a couple of months later. It was indeed the elusive Chagos Brain coral. “There’s almost no data on this coral at all, until now. This is really the first time in the history of the planet that a full genome of this coral has been made available.”

It wasn’t the only coral he’d extracted DNA from. He’d also analyzed the genomes of the Chagos Archipelago’s keystone coral species to better understand the role genetics play in its ability to survive warmer waters. “We’re looking at certain immune genes to see whether they’ve got differences in their systems, and whether that’s giving them better resilience to heating events,” Wilson says. He’s also investigating coral holobionts to see how microorganisms may play a role. Understanding these differences and complexities may have applications for coral reef resilience and recovery around the world.

Wilson uses QIAGEN’s DNA extraction kits to process his coral samples while at sea. Sometimes, he even processes samples while bobbing in one of the inflatable rafts used to visit reefs the ship can’t access.

“The great thing about the QIAGEN kits is that they come with pretty much everything you need.”

Bry Wilson

A field season thwarted by COVID-19

The program researchers headed back to the Chagos Archipelago in February 2020, just as alarming reports of COVID-19 began to emerge from China’s Wuhan province. Two days into the expedition, Wilson, along with fellow researchers Margaux Steyaert and Vivian Cumbo, dove a reef in a lagoon in the Three Brothers islands. Gray nurse sharks lurked nearby as they finned along. Nearly an hour in, their dive tanks nearing empty, the trio reluctantly began to return to the surface. As Wilson rose, he looked down into the depths – and suddenly spotted Ctenella.

“I just saw this big, beautiful-looking brain,” he says.

They quickly swam over.

“There were 10 or 15 of these corals stretching along this reef wall,” Wilson recalls. “They were the most beautiful, healthy colonies we’d seen of this coral in well over a decade. My heart was in my throat. I gulped through what little air I had left, like a kid.”

Soon after, they had to abort the expedition. While they’d been at sea, largely disconnected from the rest of the world, COVID-19 had become a global pandemic. Countries were closing their borders. Their normal route out of Bahrain was impossible. Eventually they managed to catch one of the last flights out of the Maldives.

The future of corals

Though the COVID-19 pandemic cut short the 2020 expedition, Wilson has been planning his return ever since. Until he can return to the Chagos Archipelago, he relishes the memory of their discovery. “I think that as a biologist, you just wait and dream that you’re going to have this opportunity to find something that nobody else has seen,” he says. “It was amazing.”

- Referenced in >200,000 scientific publications

- >500 consumables kit SKUs addressing extraction for samples as diverse as soil and blood

- Addressable market of >$1 billion

- Accounted for 43% of QIAGEN’s 2020 sales